Heating Day in ancient times

There was no advanced central heating system in ancient times; however, there was a day when people would burn stoves for heating.

Kailu Jie (Stove Burning Festival) fell on the first day of the tenth lunar month. As it turned cold, people would prepare lots of firewood and repair and clean their stoves to burn them for heating. Kailu means starting to use a stove. Kailu Jie marked the beginning of fighting against cold in ancient times, which is similar to the start of modern day heating in China.

“There was one thing in my family that was consistent with old folk customs in Beijing, that is the starting of burning stoves on the first day of the tenth lunar month and withdrawing them on the first day of the second lunar month in the following year. All families, including the princes’ residences, obeyed this invisible rule. There was also a routine in my family in which the underfloor heating would be turned on on the Winter Solstice.”

Jin Jishui, Records of Lives in the Princes’ Residences (Wangfu shenghuo shilu)

What kinds of utensils were used to eliminate the cold in the princes’ residences during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911)?

Heating installation in ancient time

When heating first started in the princes’ residences, major heating systems like underfloor heating, the kang bed-stove and portable hand and foot warmers played a significant role in keeping the residences warm and cozy.

Underfloor heating was realized by building underground flues using bricks and stones when constructing buildings, and burning something to heat the floor. The underground heat spreads to different chambers along the flues to formulate heat circulation, heat up floors and keep rooms warm.

The other heating installation was the kang bed-stove, the mechanism of which was similar to that of the underfloor heating. Its firing pit and flue are both set outdoors, which not only prevents smoke entering and polluting the rooms, but also prevents carbon monoxide poisoning. Compared to traditional Western fireplaces, the method of burning coal outside to warm rooms reduced fire risks.

Firing pit in the Rear Building of Prince Kung’s Palace

Firing pit in Yin’an Hall of the Prince Kung’s Palace

Yixin (Prince Kung) once wrote a poem to applaud the kang bed-stove for keeping the room as warm as spring when it snowed heavily outside.

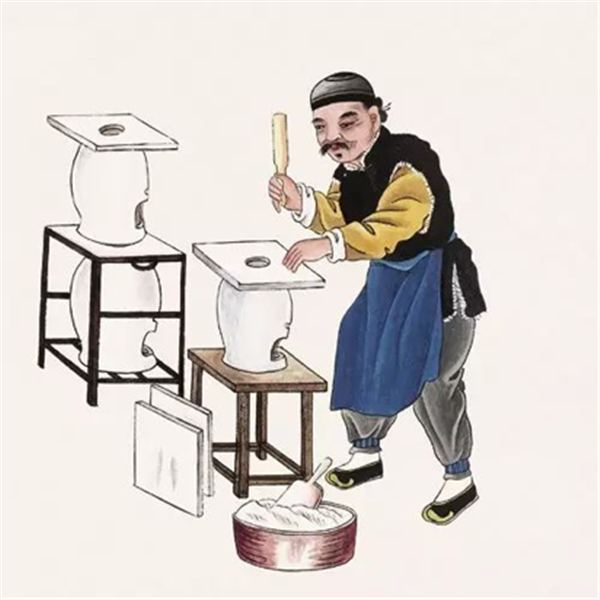

Apart from underfloor heating and the kang bed-stove, various types of stoves placed on the ground were also indispensable at the princes’ residences in winter. The white stove, which shared the same function as the modern electric heater, was favored by people living in the princes’ residences to fight against the cold.

White stove

The stove burnt on the first day of the tenth lunar month was the white stove, which was made using fagus. It was white and beautiful, ranging in different sizes and was capable of producing large fires to keep warm. The white stove could be used at the owners’ disposal, with no fixed position.

There was a person specially assigned to burn the white stove. Each room was equipped with a white stove with no chimney or air pollution. In the 1920s and 1930s, there was a famous white stove shop called Haishanchang to the south of Dengshikou.

There was also a kind of stove with chimneys popular among rich families in Beijing. The stove, which was electroplated, came in large and small sizes but was only used for heating purposes rather than cooking or boiling water. The large stove had three doors and insulation glass was installed inside it. The small stove was bucket-shaped and had an opening for coal on the top.

Aside from the large heating systems, there were exquisite and portable hand and foot warmers, not dissimilar to modern electric warmers and hot-water bottles. The hand and foot warmers were portable and warmed people’s extremities by putting charcoal inside. The foot warmer was typically cuboid, whereas the handwarmer was round or square, usually made out of copper and occasionally enameled. It had a handle to make it portable and its copper lid carved with hollow patterns to allow heat to escape.

Handwarmer inlaid with enamel artwork of Sanyang Kaitai (Three Rams Bringing Bliss), Qing Dynasty, from the collection of the Palace Museum

A brasier was another applicable heating utensil. Keeping warm with a brasier was a custom of Manchu people before they entered the Shanhai Pass in 1644. The brasier became more and more exquisite, and was usually made out of copper and had three feet and a wide edge. Some brasiers were equipped with hollowed covers to prevent sparks spilling out.

Scroll of Emperor Yongzheng (r. 1722-1735) reading beside a brasier

Yixin paid attention to life's small details and described charcoals of different shapes as beast charcoals.

Heating fee granted by the princes’ residences

Coal consumption was very high in winter, and there was a coal warehouse specifically built in the princes’ residences, which was responsible for buying, transporting, depositing and managing coal for the supply of the whole residence.

According to the Archives of the Qing Dynasty Prince Kung’s Palace, the palace’s coal warehouse would grant all in the palace with fees to buy coal, which was a popular phenomenon of the late Qing Dynasty princes’ residences.